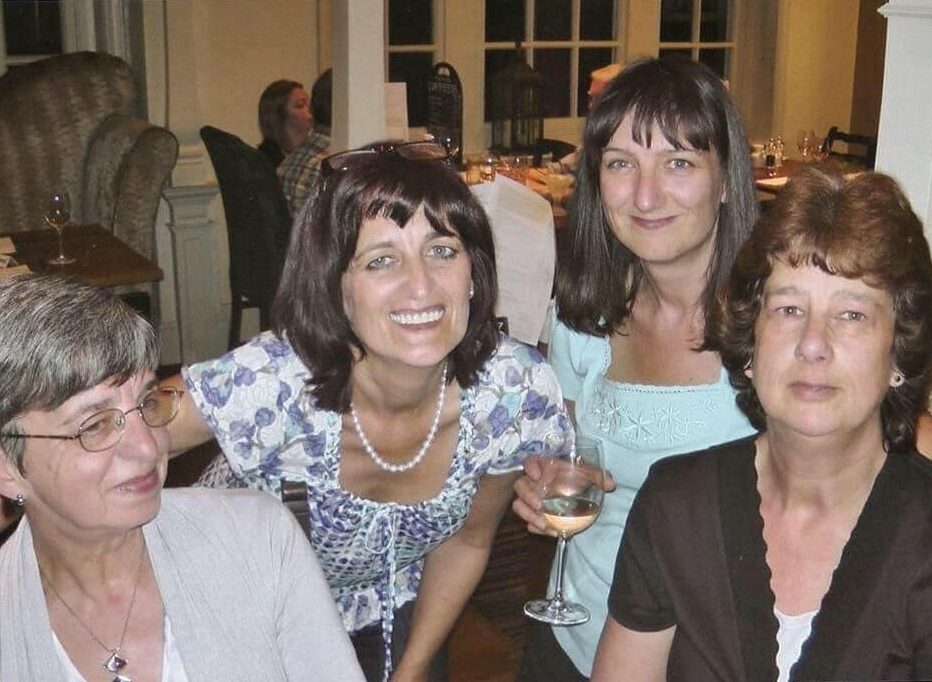

Lisa’s life changed when two of her sisters died from a hereditary aortic dissection.

As the youngest of six children, Lisa had thought it was normal to be double-jointed and ‘bendy’, like her mum and other family members. It wasn’t until her first child was born that she realised it could be a sign of something more significant.

Lisa’s first child, Zoe, was very floppy when she was born and struggled to feed and swallow.

When Zoe was slightly older, a health visitor noted that she could not remain sitting up in a high chair and that she was not crawling. She referred Zoe to a local physiotherapy and orthotics service, which helped her to get stronger.

When Lisa’s second child, Jeremy, was born, he had similar issues. Eventually Lisa and her children were diagnosed with a hereditary connective tissue disorder, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS). This is a group of conditions that can affect various parts of the body such as joints, internal organs and blood vessels, including the aorta.

Meanwhile, Lisa talked with her brothers and sisters about whether they, or their children, might have the condition.

'My sister Angela was a nurse, and she told me she would know if she had something like this. Not long after that conversation she was dead.'

Angela had died because her aorta had dissected and ruptured.

‘After Angela died, I tried to chat to the rest of the family, but it was very difficult to talk about.’

Five years later, Lisa’s sister Kirsty also died suddenly from an aortic dissection and rupture, in exactly the same part of the aorta as Angela.

‘History had repeated itself. I’d meant to see Kirsty that day and I took it very hard.’

Kirsty’s death encouraged Lisa to push harder for genetic testing. Until this point, no-one in the family had been offered testing despite their family history and diagnosis of EDS.

Lisa’s GP also referred her for an echo-cardiogram, which is an ultrasound scan of the heart. It found a small widening, or dilatation, in the same part of the aorta that had ruptured in Angela and Kirsty. Lisa’s three surviving siblings also subsequently asked for scans, which identified similar aortic dilatation in two of them.

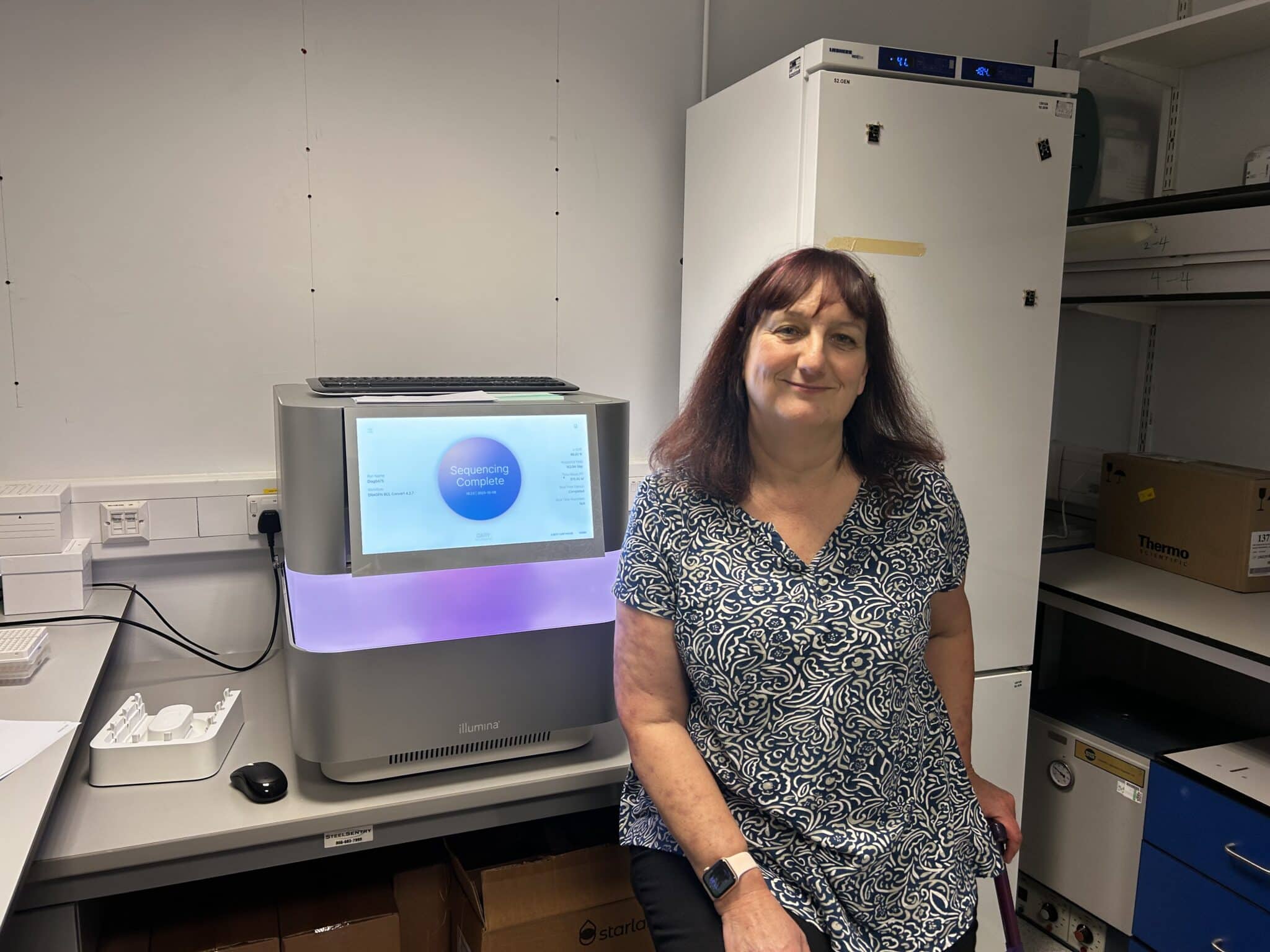

Lisa’s life has changed significantly since her family confirmed their inherited condition. She recently visited Royal Brompton Hospital’s specialist cardiac genetic laboratory, which performs genetic testing for conditions such as EDS, and shared her family’s experience of living with an inherited condition.

Clinical scientist and deputy head of the laboratory at the Royal Brompton, Matt Edwards, organised the visit for Lisa to come and see for herself how the genetic testing is done.

Matt said: ‘We’re very lucky to have a wonderful group of patients who work with us to help improve our service and it was a pleasure to welcome Lisa to the laboratory’

“We deliver all genetic testing for suspected inherited cardiac conditions for everyone in London and the South East of England – a population of approximately 19 million people – so we were able to show Lisa how the genetic testing is done and introduce her to the team. Crucially, it gave us an opportunity to hear about her experience and discuss what we can do better.”

Outside of her work with the Royal Brompton, Lisa is actively involved in research around the genetic causes of aortic dissection and leads a bereavement group for other families who have been affected by an aortic dissection.

Her work with the patient charity Aortic Dissection Awareness UK & Ireland has also helped her to learn more about the condition and come to terms with the far-reaching impact on her family. The charity highlights the importance of a diagnosis to help decisions about treatment and the timing of surgical interventions. Having a diagnosis means people can be actively monitored, make lifestyle changes, and they may have the option of surgery to prevent aortic rupture.

Lisa has also recently started working with the South East NHS Genomic Medicine Service to help encourage coroners to consider hereditary cardiac conditions, and keep samples when someone dies suddenly to enable genetic testing.